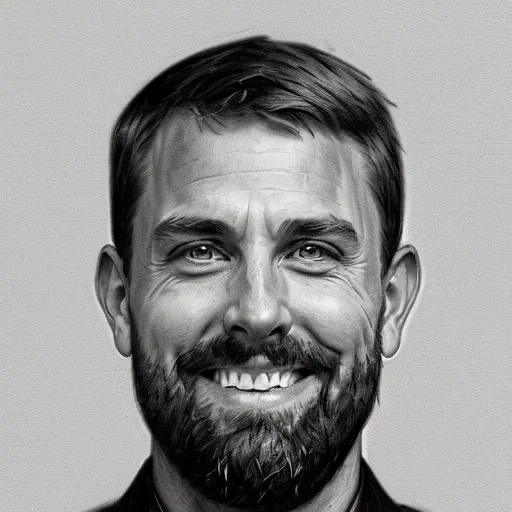

I'm Jeremy Crane. I've spent the last 20+ years building software products — from pre-revenue startups to post-IPO product lines. I trained as an engineer (physics at Bates, engineering at Dartmouth) and drifted to the product side because that's where the most interesting problems were. I've been building, organizing, and leading product teams ever since.

My Personal Product Beliefs

I've come to believe a few things about how good products get built. These are mine — shaped by 20+ years of doing this work. Like any good product, this list evolves.

No One Size Fits All

No one has a product development process that is the perfect recipe for success. What they might have is a perfect recipe for their unique set of circumstances. The best process for you is the one that aligns with the people, resources, challenges and opportunities that you uniquely face. Learn from other teams and organizations but don't follow blindly.

Organize for the Given

You can't solve all of your product problems with a better product org structure. Structure your org for what needs to be "free" and put energy into the rest. Whatever is most important to your company's success should be baked into your everyday structure. Then put effort into the edges to solve all of the inevitable "other problems."

Small Teams Build Faster

When in doubt either keep your product team small or figure out how to break it down into smaller squads. It's astonishing what two good developers, a PM, and a designer can bring to life and how quickly they can do it.

Iteration Is Hard but Worth It

The desire to iterate and continuously improve your product is rarely in question. In practice this can be very hard to execute on within an organization. Whether it's a fear of missing the mark out of the gate or pressure to move onto the next thing.

AI Is Going to Change Everything

We are on the precipice of a massive societal change. Our little world of software development is no different. The impossible is now possible and everything we built before will likely be rethought.

User Centric Design Always Wins

A well thought out and simple design will always be more successful than the tool that does it all. Highly opinionated products are the easiest for users to quickly adopt and often the most retentive.

Clarify Ambiguity

The single most underrated product skill. Not eliminating ambiguity — that's impossible — but naming it explicitly, so the team is working on the same version of the problem. Most product debates are actually disagreements about which problem you're solving, dressed up as debates about the solution. A PM who can say "we have three different assumptions here and they lead to three different products — let's decide which one we're making" is worth their weight in gold.

Marketing Is the Product

In the best software companies, the line between marketing and product is blurry on purpose. The onboarding experience is a marketing function. The in-app copy is a marketing function. The first email a new user gets is a marketing function. The moment a product team stops caring about how the product is discovered, explained, and experienced before signup — that's the moment marketing and product start working against each other instead of together.

Reduce Friction. Anticipate Needs. Exceed Expectations.

This is the hierarchy. In that order. Most product teams jump straight to "exceed expectations" and build elaborate features while ignoring obvious friction. Before you wow someone, make sure they can actually use the thing. Before they use the thing, make sure you anticipated what they'd need next without making them ask for it.

Other Product Beliefs I Love

Ideas and frameworks from brilliant thinkers that deeply influence how I work. Credit where it's due.

Declarative Is the New Imperative

Dharmesh Shah's framing is the clearest articulation of the defining product design shift of this era: from task-oriented (imperative) software to goal-oriented (declarative) software. "Click here, then here, then fill this in, then submit" is the old model. "Tell me what you want to accomplish" is the new one. Every existing product is ripe for rethinking along this axis.

Credit: Dharmesh Shah, HubSpot co-founder. Watch the original talk.

IC Users Over Middle Managers

When you're doing customer discovery, talk to the people who actually use the product. Not the VP who bought it, not the manager who manages the people who use it — the person whose hands are on the keyboard. Middle managers tell you what they think you want to hear and describe problems from a distance. ICs tell you what actually happens and what actually hurts. The closer you are to the actual usage, the better your product will be.

Credit: Karri Saarinen, co-founder of Linear. Linear's core product philosophy is to build for the makers — the ICs who use the tool daily — not the managers who purchase it.

Value + Viability — and AI Needs Feasibility Too

Marty Cagan's four-risk framework — value, viability, usability, and feasibility — is the foundational lens for product discovery. The PM owns value and viability; the designer owns usability; the tech lead owns feasibility. It's a great model. The extension worth making for AI products: feasibility is dramatically underweighted by most product teams right now. Hallucination rates, latency, cost-per-query, edge case failure modes — these aren't engineering footnotes, they're core product constraints. Feasibility has always been in Cagan's framework. AI just made ignoring it much more expensive.

Credit: Marty Cagan, Silicon Valley Product Group. See INSPIRED and The Four Big Risks.

Slime Structures

Most org structures are drawn on whiteboards and presented as fixed. The reality is that good product orgs are more like slime — they should flow to fill the shape of the actual problems in front of them. The structure that works at 10 engineers breaks at 30. The team that moves fast pre-PMF needs to think differently post-Series B. Stop treating your org chart like a constitution. Treat it like a working hypothesis.

Credit: Alex Komoroske. See his presentation Coordination Headwind — How Organizations Are Like Slime Molds.

Kill Kayfabe

Professional wrestling has "kayfabe" — the code of silence that keeps the audience believing the show is real. Applying this to software companies: the polished roadmap that's actually fiction, the "data-driven" decision that was made in a conference room, the product update that's really a sales feature nobody asked for. Good product leaders kill kayfabe internally. They name what's actually happening, even when it's uncomfortable.

Credit: The concept of "kayfabe" applied to institutional dynamics was popularized by Eric Weinstein in his 2011 Edge.org essay.

Adjacent Possible with a Low-Fidelity North Star

The "adjacent possible" — the set of things that are exactly one step away from what currently exists — is one of the most useful mental models in product strategy. The concept was coined by complexity scientist Stuart Kauffman and popularized for innovators by Steven Johnson in Where Good Ideas Come From. The best product roadmaps don't pretend to know what the product looks like in three years. They hold a blurry, low-fidelity North Star (directionally right, not pixel-perfect) and execute aggressively on the adjacent possibilities closest to them right now. The North Star keeps you honest. The adjacent possible keeps you grounded.

Credit: Stuart Kauffman (original concept); Steven Johnson, Where Good Ideas Come From (2010).

ABCDE Vision

A useful test for whether your product vision is actually useful vs. decorative. A good vision is:

- Achievable — not "change the world" vague, but concretely within reach

- Bold — directionally ambitious enough to inspire

- Clear — your team can repeat it without looking at the slide

- Differentiated — explains why you and not someone else

- End-to-end — describes the full experience, not just a feature set

Most product visions fail C and E. They're internally understood but can't survive a game of telephone.

Credit: Prodify and their advisory team, including Sara Zalowitz, who coined the "ABCDEs of a Product Vision" framework. See Prodify.

Career Arc

The Foundation

Studied physics, then engineering, then eventually business. Started at Ford Motor Company, then early analytics and digital media at Compete. This is where the analytical rigor and business instincts were built.

The Formative Years

oneforty — a VC-backed startup that was acquired by HubSpot — then HubSpot, where I served as VP of Product through post-IPO, leading a $300M ARR product line. This is the "grew up here" chapter.

The Portfolio

IndigoAg, Dockwa/Wanderlust Group, Jasper, and now Ankored. Different industries and stages, same craft applied repeatedly.

Other Parts of My Story

Bates College (BS Physics). Dartmouth College, Thayer School of Engineering (BE + MEM). University of Michigan, Ross School of Business (MBA with distinction).

New England native — grew up in New Hampshire, landed in Boston, never left. I raced Division I alpine at Bates but left the gates behind a long time ago. Now I just ski for the joy of it, every chance I get.

I ride bikes — road for years, but more mountain these days. Love playing in the woods.

I read too much sci-fi and I think too much in general. Sometimes those are the same thing.